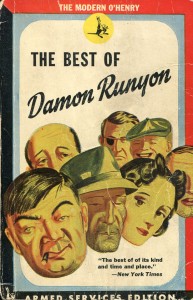

Guys and Dolls is based on short stories by Damon Runyon, a newspaper columnist whose thirty-year career was at its peak in the 1930’s. The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik provided this appreciation of Runyon’s work in a 2009 casual:

Of all the pop formalists, the purest and strangest may be Damon Runyon, the New York storyteller, newspaperman, and sportswriter who wrote for the Hearst press for more than thirty years, inspired a couple of Capra movies, and died in 1946. Runyon’s appeal … came from his mastery of an American idiom. We read Runyon not for the stories but for the slang, half found on Broadway in the nineteen-twenties and thirties and half cooked up in his own head. We read Runyon for sentences like this: “If I have all the tears that are shed on Broadway by guys in love, I will have enough salt water to start an opposition ocean to the Atlantic and Pacific, with enough left over to run the Great Salt Lake out of business.” And for paragraphs like these, at the beginning of “Lonely Heart”:

Of all the pop formalists, the purest and strangest may be Damon Runyon, the New York storyteller, newspaperman, and sportswriter who wrote for the Hearst press for more than thirty years, inspired a couple of Capra movies, and died in 1946. Runyon’s appeal … came from his mastery of an American idiom. We read Runyon not for the stories but for the slang, half found on Broadway in the nineteen-twenties and thirties and half cooked up in his own head. We read Runyon for sentences like this: “If I have all the tears that are shed on Broadway by guys in love, I will have enough salt water to start an opposition ocean to the Atlantic and Pacific, with enough left over to run the Great Salt Lake out of business.” And for paragraphs like these, at the beginning of “Lonely Heart”:

“It seems that one spring day, a character by the name of Nicely-Nicely Jones arrives in a ward in a hospital in the City of Newark, N.J., with such a severe case of pneumonia that the attending physician, who is a horse player at heart, and very absentminded, writes 100, 40 and 10 on the chart over Nicely-Nicely’s bed.

It comes out afterward that what the physician means is that it is 100 to 1 in his line that Nicely-Nicely does not recover at all, 40 to 1 that he will not last a week, and 10 to 1 that if he does get well he will never be the same again.

Well, Nicely-Nicely is greatly discouraged when he sees this price against him, because he is personally a chalk eater when it comes to price, a chalk eater being a character who always plays the short-priced favorites, and he can see that such a long shot as he is has very little chance to win. In fact, he is so discouraged that he does not even feel like taking a little of the price against him to show.

Afterward there is some criticism of Nicely-Nicely among the citizens around Mindy’s restaurant on Broadway, because he does not advise them of this marker, as these citizens are always willing to bet that what Nicely-Nicely dies of will be overfeeding and never anything small like pneumonia, for Nicely-Nicely is known far and wide as a character who dearly loves to commit eating.”

Here are all the elements of Runyon’s voice: the perpetual present tense, the world without conditional moods, the stilted, over-elaborate attempt at precision, and, above all, a way of life and a social class evoked purely through vernacular. And then there is the unchanging, perpetually nameless and anxious-eager Narrator, with his warily formal diction and his cautious good manners—a born exquisitist telling stories at Lindy’s, trying to define a chalk-eater while using the mild word “discouraged.” The Narrator is, crucially, one of the lowest-status figures in Runyon’s bicameral world, where the petty hustlers and horseplayers who haunt Lindy’s by day are set against their sinister opposites, hit men and gangsters, who mostly hail from Brooklyn and Harlem and arrive at night. (The chorus dolls of the Hot Box night club move between the two.) “One evening along about seven o’clock I am sitting in Mindy’s restaurant putting on the gefilte fish, which is a dish I am very fond of, when in come three parties from Brooklyn wearing caps as follows: Harry the Horse, Little Isadore and Spanish John”—that’s the essential Runyon opening. The Narrator has to be careful; he is telling stories, often, of what elaborate politesse it takes to keep from getting killed, and his care is the source of a lot of his comedy. A wiseguy on the lower end of the totem pole is of necessity an expert in courtesy. (And Runyon’s world, let’s note, is not Times Square and Forty-second Street, where the kids and the grind houses and the freak shows were, but up at Broadway around Fiftieth, where the night clubs and the restaurants and the drugstores were.)

Damon Runyon’s Broadway is also evoked vividly in a colorful essay on the site Talkin’ Broadway, and columnist Dan Rodricks in the Baltimore Sun describes Runyonland as a “bygone, neon-bright underworld of theatrical agents, showgirls, relatively harmless (by today’s standards) gangsters, bookies, gamblers, bunco artists, vice cops, restaurateurs, singers, dancers, bartenders and nobodies who became somebodies once Runyon met them, listened to them and wrote their stories.”

Damon Runyon’s Broadway is also evoked vividly in a colorful essay on the site Talkin’ Broadway, and columnist Dan Rodricks in the Baltimore Sun describes Runyonland as a “bygone, neon-bright underworld of theatrical agents, showgirls, relatively harmless (by today’s standards) gangsters, bookies, gamblers, bunco artists, vice cops, restaurateurs, singers, dancers, bartenders and nobodies who became somebodies once Runyon met them, listened to them and wrote their stories.”

“With great style,” says Rodrick, Runyon “did something that hadn’t been done much in American newspapering — he wrote from the street. He wrote about people who, because of their low station or lack of public office, never once dreamed of getting their names in the newspaper. He didn’t write about the major political issues of the day, but how people worked, played, dreamed and schemed. He put flesh and blood where there had been only the vaguest outline of humanity.”

When does Guys and Dolls take place? The script provides only one explicit clue, in the song “Take Back Your Mink,” when Adelaide recounts the gifts bestowed on her by her generous gentleman friend back in “late forty-eight.” 1948 seems a bit late, since so much of Runyon’s world is shaped by the social phenomena of the early 1930’s, an era when the converging forces of the Depression and Prohibition provided the perfect spawning grounds for small-time crooks and hard-luck hustlers. Of course, Cole Porter’s Kiss Me Kate (1948) features two dice-playing mugs with Runyonesque diction who memorably exhort us to “Brush Up Your Shakespeare.” It appears this particular species of low-life could be found on the streets of New York through the 1930’s and 40’s, though by 1950, when Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows penned the libretto for Guys and Dolls, these characters were familiar archetypes.