This is the first in a series of posts inspired by this year’s Musical Theater Educators Alliance conference. Every year for the past sixteen years, leading pedagogues from musical theater training programs around the world have gathered to share presentations on their most effective methods. This year, our meeting was hosted by New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development, home to the Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions.

This is the moment,

This is the time…

Frank Wildhorn’s lyrics from Jekyll and Hyde speak of the sense of excitement we experience as we are about to begin something important. Dr. Jekyll is facing what Alexander Technique teachers would call a “critical moment” – “critical” in the sense of “crisis,” a turning point when future outcomes will be determined by present choices. Finding EASE in those critical moments is a key to success, but since critical moments are often accompanied by stress and tension, ease in the critical moment can be elusive.

Many performing arts schools include training in Alexander Technique as part of their program of studies, and many performing arts teachers have had some training in Alexander Technique. Alexander Technique focuses on how we use our bodies, particularly at times when we are under pressure to do something stressful or challenging, and this makes it especially useful to singers, actors, dancers and instrumentalists seeking to improve their performance. AT helps the student become aware of unconscious physical habit patterns that add unnecessary tension and effort, and re-educates performers to achieve more optimal use of their bodies. AT has benefits that extend to people in all walks of life, and many individuals have derived great therapeutic benefit from the technique. Performers who are able to incorporate the Alexander Technique notice greater poise and ease, less pain and tension, and an expanded sense of possibilities.

Many performing arts schools include training in Alexander Technique as part of their program of studies, and many performing arts teachers have had some training in Alexander Technique. Alexander Technique focuses on how we use our bodies, particularly at times when we are under pressure to do something stressful or challenging, and this makes it especially useful to singers, actors, dancers and instrumentalists seeking to improve their performance. AT helps the student become aware of unconscious physical habit patterns that add unnecessary tension and effort, and re-educates performers to achieve more optimal use of their bodies. AT has benefits that extend to people in all walks of life, and many individuals have derived great therapeutic benefit from the technique. Performers who are able to incorporate the Alexander Technique notice greater poise and ease, less pain and tension, and an expanded sense of possibilities.

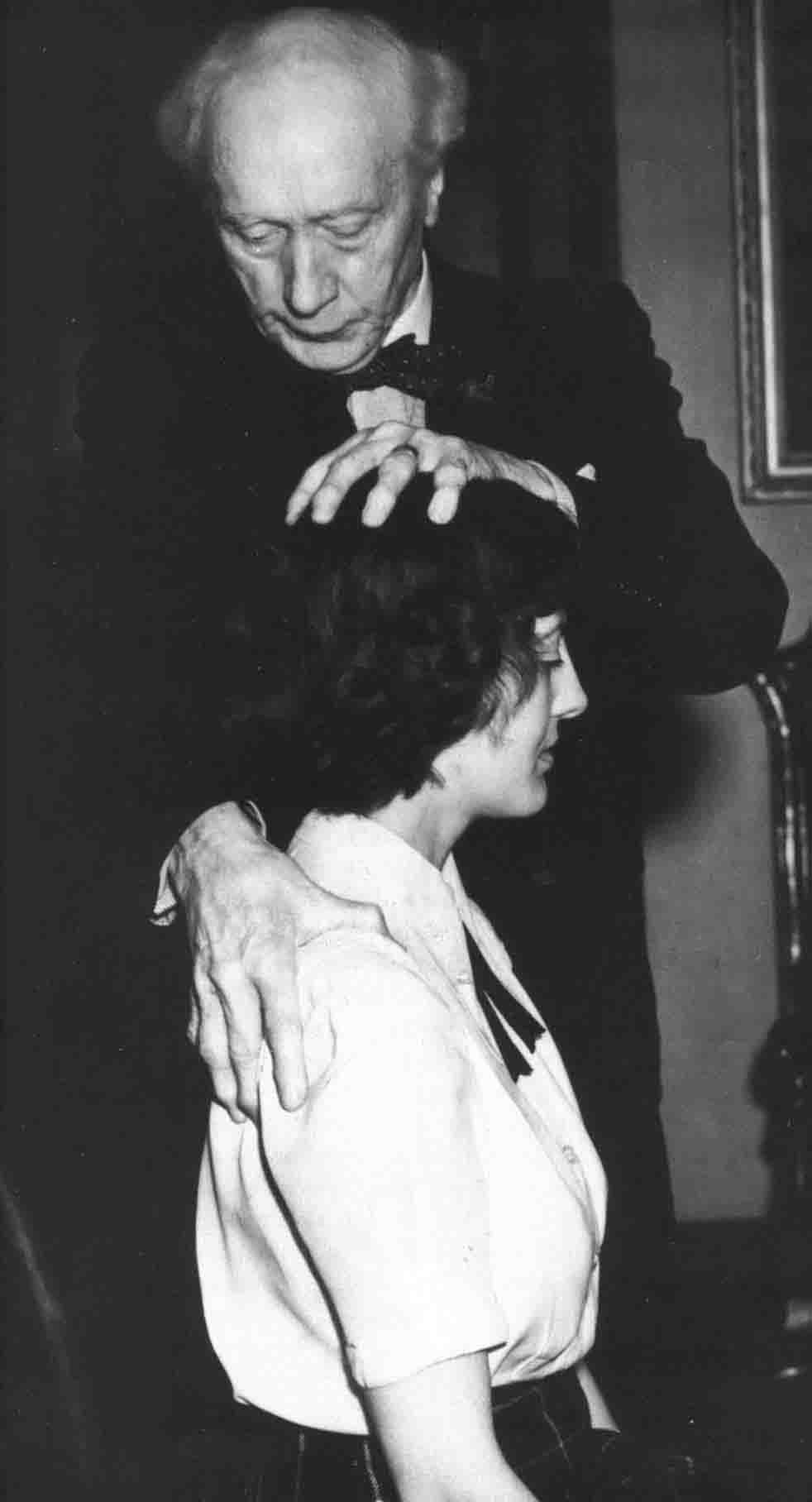

What is Alexander Technique? It is a way of thinking about movement and posture, a way of moving, a re-education of the body. F. Matthias Alexander, who originally discovered and articulated the principles in the technique that bears his name, was a public speaker who lost his voice; in his search for the cause of his problem, he discovered certain patterns of movement, ways he used his body while speaking, and restored his voice by training himself to use his body differently. Self-awareness of one’s own patterns of use is a key first step in an education in the Alexander technique.

When Alexander Technique teachers speak of the “critical moment,” they are describing the moment that occurs right before you begin an activity. As you are about to do something, your body prepares itself unconsciously, as a reflex; often, this includes a slight contraction of the neck and spine, a bracing up of the joints and a decreasing awareness of your senses. For singing actors, this moment occurs as you begin to sing a song, speak a speech or play a piece of music – the moment when you make the transition from “not performing” to “performing.” At that critical moment of beginning, certain things happen unconsciously in your mind and body. You think “get ready, get set, go,” but as you “get set,” you lose the freedom that is essential to beginning your activity with ease and poise. You think, “I’m going to bear down, try harder, make more of an effort,” all in the name of achieving success, but all these thoughts, and the subconscious physical adjustments that accompany them, are diminishing your chances of achieving the very success you seek.

I have found it very helpful to think of the beginning of each new phrase – in SAVI parlance, each “ding” – as a kind of critical moment in the journey of the song. As you finish doing one thing (singing a phrase, playing an action) and prepare to do the next thing, there is a tendency to hold over the effort and tension associated with the previous phrase. Gwen Walker, in her marvelous workshop at MTEA, describes this using the analogy of playing the piano. Muscles, she says, are like piano keys, and you need to release them before you can press them again. There is much to be gained by thinking of each new phrase as a new event, and for the SAVI singing actor who seeks to work “phrase by phrase,” the onset or beginning of each new phrase is a critical moment, the moment when you cease to do the dramatic action and behavior associated with the previous phrase and make a conscious change or choice to begin to undertake the behavior associated with the action of the upcoming phrase.

The study of Alexander Technique is designed to impart a sense of ease at those critical moments. You come to learn that you have a choice at the critical moment, and learn to inhibit or adjust the unconscious habits that interfere with your ability to make the optimal choice.

It is often maddeningly elusive to try to talk about AT, and even bright and eager undergrads can become impatient as they begin to become acquainted with the method. AT teachers can compound this problem when they adopt an exotic air of mystery in their demeanor. There is indeed something mysterious and marvelous about AT, but it is, at the same time, quite simple and practical. Indeed, some of the thought patterns we associate with learning and performing – for instance, the idea that in order to succeed, you need to “try harder” – have been found to be destructive habits of thinking that constrain your ability to be free and easy at the critical moment.

How, then, can one attain ease at the critical moment? One powerful strategy I learned about in Gwen Walker’s session: Come to your senses. “Effort causes you to not notice yourself. Asking the student to notice something, to attend to the quality of himself, is an effective way of reducing tension,” according to Gwen. As you approach the critical moment, allow yourself to take in as much sensory information as you can, not only from your body, but from your companions (your partners in a scene, for instance) and your environment. When we sing, we are transmitting information, sending it out to be seen and heard by others; you will experience greater ease if you allow yourself to RECEIVE as well as TRANSMIT. The moment when you take a breath, allow yourself to also take in information.

AT teaches us that how we begin something is enormously important to how we will do what we’ve begun. This is true whether you’re talking about getting up from a chair, climbing a step, or taking a breath to begin to sing a phrase. The moment just before we begin – that instant of “onset” when we make the transition from the previous thing to the impending next thing – is critical to the qualities we will bring to it.