The face is the ultimate “organ of expression.” Its chief purpose is to transmit information for the benefit of those around you – I’m friendly, please approach; I’m scary, better step back; I’m lost, can you help me?; I’m in the mood for love, are you? Communication like this is central to our survival as a species. How else to explain the exquisite network of muscles that have developed on the face for the purpose of transmitting facial expressions?

Studies by psychologists have shown that our words account for a small percentage of our actual communication. Vocal tone and facial expression account for the majority of the information we transmit. If the words you’re saying and your tone and expression don’t match those words, people are more likely to disregard your words and heed your non-verbal messages. (Imagine someone saying “I love you” while their facial expression is tense and troubled, for instance. Which would you believe – the words or the face?)

All this is crucially important information for the singing actor, and yet it’s information that many singing actors seem to be hesitant to use to their advantage. Some of my students are initially surprised by the idea they need to master the messages that their faces transmit. The idea that there might be a “technique” associated with the face seems almost like heresy. After all, the face is supposed to work unconsciously, right? All those muscles, they’ll do what they’re supposed to and send the right message if I’m feeling the right feelings – isn’t that how it works?

All this is crucially important information for the singing actor, and yet it’s information that many singing actors seem to be hesitant to use to their advantage. Some of my students are initially surprised by the idea they need to master the messages that their faces transmit. The idea that there might be a “technique” associated with the face seems almost like heresy. After all, the face is supposed to work unconsciously, right? All those muscles, they’ll do what they’re supposed to and send the right message if I’m feeling the right feelings – isn’t that how it works?

Acting teachers warn their students about the sin of “mugging,” making faces to show emotions they don’t feel. “Leave yourself alone!” is one of the central tenets of Sanford Meisner’s approach to acting; trying to manufacture emotion or counterfeit its expression on the face is one of the cardinal sins an actor can commit in an acting studio environment.

Wesley Balk’s analysis of the face and its role in the expression of emotion while singing remains seminal and enormously important. He writes about this with great detail in his 1985 book Performing Power, describing it as “controversial” but noticing that students with a background in singing were more open to exploring the technical aspects of facial communication than those with a background in acting:

“The idea of making faces, grimacing to convey emotions, or even working with facially oriented techniques is anathema to those who have studied and worked in American theater traditions. … Actors were more resistant than singers because [of these] … preconceived notions… Singers, being involved in a highly technical act to begin with, accepted the concept more readily. … [T]he change and growth made available through the exercise and development of the facial/emotional mode have been genuinely astonishing.” (141-2)

Psychologist Paul Ekman has undertaken decades of noteworthy research into the psychology of facial expression, and demonstrated that the conscious use of certain facial muscles can arouse organic emotional responses. Susanna Bloch built on Ekman’s findings to develop the technique known as Alba Emoting, an innovative “psychophysical” approach designed to help actors create and control emotion.

Psychologist Paul Ekman has undertaken decades of noteworthy research into the psychology of facial expression, and demonstrated that the conscious use of certain facial muscles can arouse organic emotional responses. Susanna Bloch built on Ekman’s findings to develop the technique known as Alba Emoting, an innovative “psychophysical” approach designed to help actors create and control emotion.

This means, when I hear an acting teacher rail against paying conscious attention to the face as an organ of expression, I take those objections with a grain of salt. The work of Balk, Ekman and Bloch, supported by my own experience working with students in the studio for several decades, tells me I’m on solid pedagogical ground.

One thing my own experience has taught me is that singers who simply “leave their faces alone” often wind up expressing very little apart from the effort of singing, even if they’re in a strong state of emotional arousal. The facial distortions that are the result of the effort of singing are further compounded by the natural tendency (particularly evident in adolescents) to want to conceal rather than reveal our innermost feelings. Singers need help becoming familiar with the workings of the face, exercising and toning those muscles so that they are flexible and expressive and learning how to counteract the distortions that singing often produces.

Here are the ways I encourage my students to put this knowledge to use:

1. Warm up and condition.

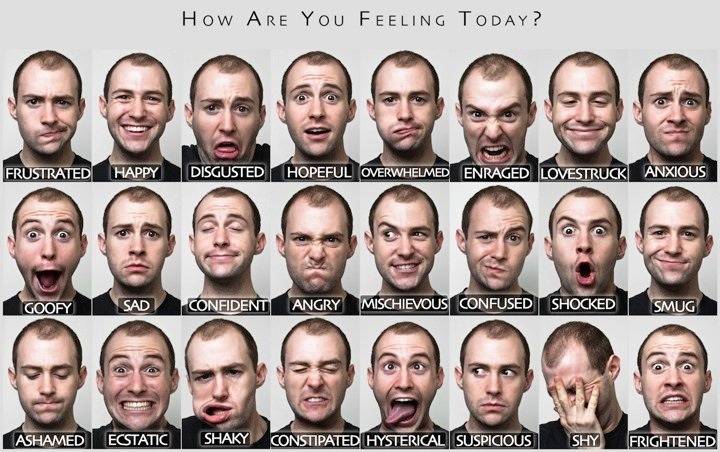

The face is an important part of the SAVI Workout, and you can begin to improve your facial expression using these techniques. Use a “facial flex” (sometimes called “gurning”) to stretch and energize every muscle in your face. The SAVI Workout slides include a mini-lesson in facial anatomy to help you isolate various areas of the face and give them all equal attention. Collect some photographs of faces in extremes of emotional expression and try to mimic the facial muscles used in the photos. If you want to be comprehensive in your approach, gather faces associated with the most common emotional states (Ekman focuses on the emotions of anger, fear, happiness, sadness, disgust, and curiosity in his studies; Bloch’s basic six are tenderness, eroticism, anger, fear, sadness, and joy) and try them on like “facial masks.” Spend part of the beginning of every practice session “turning your face on,” and give yourself a quick “facial flex” right before you take the stage to sing.

The use of the eyes within the facial mask is so important that I’ll devote a future post specifically to the eyes. During your warm-up, though, you should definitely be attentive to the muscles that control your gaze as well as the muscles around the eye that control your eyelids and the “squint” muscles below the eyes. Squinting is a common unconscious side-effect of vocal effort and diminishes the expressiveness of the eye. Practice singing with an open, expressive eye, and move your gaze about in different directions to cultivate a “thinking eye.”

2. Explore deliberately.

Whether you’re vocalizing to build technique or working on repertoire, it’s always a good time to explore how you might use your face while singing. Deliberately activate difference muscle groups while you sing. Bring out your pictures and try on some of those facial masks, using one for each phrase. It doesn’t matter if the faces match the emotions of the repertoire exactly; indeed, there’s plenty of room for creative discovery by trying out faces that you might initially think don’t “fit.” Use a mirror or, better yet, a video camera to get feedback on what your face is saying. A full-length mirror is commonly part of any vocal practice room, but watching yourself in the mirror requires a kind of split attention which can be confusing and inhibitory; video is better because you can watch yourself calmly after the fact, rather than while you’re in the midst of being expressive, and rewind and replay as often as needed til you see clearly what you need to change.

3. Craft thoughtfully.

Make decisions about how you’re going to use your face and when you’re going to change your facial expression. Facial expressions usually change “at the ding,” that is, when a new phrase begins, and remain relatively unchanged for the duration of the phrase. Deciding to make a change is sometimes all you need to do; it may not be necessary to decide the exact nature of the facial expression you’re going to use next so long as you make a change. An effective singing-acting performance has SPECIFICITY, and this pertains to the use of your face, for sure. If you are deliberate about making some changes in your facial expression, this will help you to achieve VARIETY in your performance. And it’s always important to work patiently and persistently with each expression until each of your choices has AUTHENTICITY, the quality of truthful expression. To be ready for performance, you will need to have practiced the coordination required to choose your facial expressions and change them at the “dings.”

Your singing acting will take a big leap forward if you condition your face so that it’s supple and strong when you want to express feelings. Try to expand your facial vocabulary of expressions by imitating examples form real life. And incorporate decisions about how you’ll use your face and eyes into your performance plan. These three steps will help you take your singing acting to a whole new level!

Thanks for this post. Great points about the face conveying vocal technique vs. connected emotion, and the psycho-physical connection of facial expression and truthful emotional arousal.

Jerry, thanks for your comment! I’ve always found working with the face to be richly productive, and I’ve seen remarkable results from students who’ve incorporated ten minutes a day of facial flex and conscious facial use into their daily workout/practice routine. I think your students will too!