The month of June has just begun. Out in my garden on this first day of June, raspberries are fruiting in rude profusion. Lavender that I thought had been killed off by an unusually harsh winter has not only sent out new leaves but its first fragrant flowers. Roses on a neighbor’s bush are spilling over my back fence, triumphing over her futile efforts to prune it back last fall. Early lettuce and radishes have already found their way from the garden to my table. The first day of June is a feast for the senses, delighting the eye, the nose and the tongue.

All of which puts me in mind of Oscar Hammerstein’s lyric from the 1945 musical Carousel:

June is bustin’ out all over,

June is bustin’ out all over,

All over the meadow and the hill!

Buds’re bustin’ outa bushes,

And the rompin’ river pushes

Ev’ry little wheel that wheels beside a mill.

June is bustin’ out all over.

The feelin’ is gettin’ so intense,

That the young Virginia creepers

Hev been huggin’ the bejeepers

Outa all the mornin’-glories on the fence.

Because it’s June!

June, June, June–

Jest because it’s June– June–June!

(Read the complete lyric here and listen to the soundtrack of the 1994 Broadway revival, sung by Shirley Verrett with a much younger Audra McDonald in the role of Carrie Pipperidge.)

I suppose you can tell I’m really feeling this June thing. But chances are you’re not. If you’ve thought about this song at all, I’m guessing you probably think it’s an old-fashioned lyric sung in by an old lady with an old-fashioned voice. The language that I find so original and full of character (“huggin’ the bejeepers outa all the mornin’-glories on the fence”) might just as easily be seen by you as quaint; likewise, the colloquial regional dialect (the dropped g’s, the phonetic spellings like “hev” and “outa”) that is a trademark of so many Hammerstein lyrics. The music is definitely old-school, a vigorous polka tempo, and even if you go for this kind of thing, you could find yourself succumbing to the temptation to deliver the song with generalized gusto but without much attention to the particular images and details that make it fresh.

To sing Hammerstein’s lyric (indeed, to sing any lyric), you must awaken yourself to the truth it conveys, and that means awakening your senses. In the song, Nettie Fowler is describing the sights and sensations of an early June day in Maine, and the joy that stirs in the heart to know with certainty that the rough winter is past and the next few months will bring a bounty of seasonal pleasures. Hammerstein was a man of the land, making his home on a farm in Doylestown (not far from me) where he took refuge from the slings and arrows of his show business career in Manhattan, and the delight he takes from nature is evident in this and many other lyrics he wrote.

It’s a challenge worthy of a fresh June morning: how can the SAVI singing actor breathe life into this classic musical theater song? What words of wisdom can the coach or director offer to guide the singing actor to a successful performance?

Stanislavski’s “six fundamental questions” are an excellent place to start:

- Who am I

- Where am I?

- When am I here?

- Why do I come here?

- What am I here to do?

- How will I do it?

Getting answers to these fundamental questions will help us dispel the “old lady” stereotype, for starters. The libretto tells us the character of Nettie in Carousel is the proprietor of “Nettie Fowler’s Spa.” The twenty-first century listener may think a “spa” is a posh health resort, but Nettie’s spa, a weathered clapboard building on the Maine coast, appears to be more like a diner, a place where the hungry watermen of the town gather for their morning coffee and donuts after rising before dawn to dig for clams. Judging from the action of the scene, Nettie is the hard-working cook, supported by a couple younger women (including Carrie Pipperidge) who serve and clean up. But that doesn’t make her an old lady.

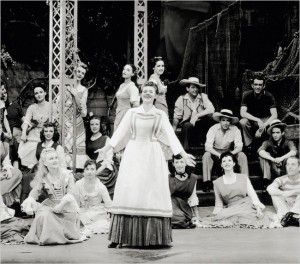

Christine Johnson, who originated the role of Nettie when The Theatre Guild premiered Carousel in 1945, was in her early thirties, as was Claramae Turner, who played the role in the 1956 film adaptation of the musical. A woman in her early thirties still has plenty of vigor and sensual appetite, though she is undoubtedly more mature and worldly-wise than girls like Julie and Carrie (teenagers or in their early twenties). More recent audiences may have seen Patricia Routledge as Nettie in the National Theatre’s landmark 1992 revival, directed by Nick Hytner, or Shirley Verrett in the 1994 Broadway transfer of that same production; both of these actresses were in their sixties when they played the role. What led Hytner to re-conceive the role as being several generations older than the authors originally envisioned her? I think it’s at least partially about the vocal style the role requires, especially in the song “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” a song of advice and consolation that Nettie sings to Julie after the ghastly suicide of her husband, Billy. Nettie traditionally sings in a mature “legit” mezzo-soprano or contralto that, to our present-day ears, is the old-fashioned sound of an old lady. But I think there’s great dramatic value in seeing Nettie as someone in the prime of her life rather than its twilight.

In the scene leading up to “June,” the hungry watermen arrive at the spa, demanding their doughnuts and apple turnovers, and the girls of the spa rebuff them with spunky flirtatiousness, scolding the boys for their impatient rudeness. When Nettie arrives with coffee and doughnuts, the girls complain that she appears to be giving in to the rowdy boys’ demands, but she is like an indulgent, affectionate mom, generously acknowledging that boys always act this way at this time of year. “It’s like unlockin’ a door,” she says, “and all the crazy notions they kep’ shet up fer the winter come whoopin’ out into the sunshine.” Cue the orchestra, as she starts with a lyric that describes March’s blustery weather and how the promise of spring has kept everyone waiting through April and May for the inevitable arrival of June and its fertile promise.

Answering the fundamental questions, while important and terribly useful, doesn’t give us all the information we need. After all, the SAVI singing actor’s job is to “create behavior that communicates the dramatic event phrase by phrase.” It’s crucial that you look at the song in this detailed way, phrase by phrase, paying particular attention to the opportunities each phrase offers and the ways in which is may differ from previous phrases.

Taking this kind of close look quickly shows that “June” is about more than little green shoots stirring in the garden. Turns out that the animal kingdom is equally stirred by the changing seasons, and that evidence of fecund eagerness can be seen among the rams and ewes in the field and the fishes in the sea. Nettie goes on to acknowledge the effect that the changing seasons have on the men and women of the community, first evidenced in affectionate behavior – “Ma is getting kittenish with Pap” – but soon apparent in the appearance of carnal appetites, as the watermen “are payin’ court” to the ladies because they “hanker for a comfort they can only find in port.” Carrie chimes in with a stanza about “lady fish… wishin’ that a male would come and grab her by the gills,” and Nettie’s final stanza conjures up visions of couples on a beach:

“From Penobscot to Augusty, all the boys are feelin’ lusty

And the girls ain’t even puttin’ up a fight.”

Holy moley! This is no vague pastorale, no perky parade of pretty pictures sung to an oom-pah beat. It’s practically an orgy by the time we get to the dance break! Each image has a particularity about it, a vivid clarity and specificity that unfolds with a logical progression the singer needs to understand in order to “put over” the dramatic event of the song for the listener.

So: a specific understanding of the dramatic event and the phrase-by-phrase unfolding of the lyric is essential if you want to put the song over with freshness and particularity. Along with understanding, though, you’re going to need musical theater technique. In particular, you’ll need strong diction to deliver this lyric in a way that takes full advantage of its onomatopoeia. You’ll need an easy, unbraced physicality with alert senses, always a challenge for the singer, whose tendency is to brace up in a state of “fight or flight” readiness when it’s time to belt out a big number. And you’ll need to be prepared to create behavior with your face, eyes, voice and body that helps to tell the story, making specific adjustments in your behavior at the onset of each new phrase to help the spectator understand how the current phrase differs from the preceding phrase. All these attributes can be cultivated through patient, persistent, purposeful practice, and when you’ve got a strong singing-acting technique to “put over the lyric” and support the unfolding dramatic event, the results will be “fresh and alive,” just like a June day on the coast of Maine.

The SAVI Savant loves musicals and offers techniques, tips and tools for the serious singing actor. Like what you’ve just read? Leave a comment, and head over to The SAVI Singing Actor website (www.savisingingactor.com) to sign up for my weekly newsletter.