There’s not much literature on voice training specifically calibrated to the needs of the singing actor, and that makes the arrival of “So You Want To Sing Music Theater,” a new book “developed in coordination with” the National Association of Teachers of Singing, something to sing about! NATS has taken considerable strides in its approach to the training of singers for the stage. It seems not that long ago that many voice teachers regarded “belting” as the devil’s work, and musical theater programs were encumbered with tenured voice faculty whose old-fashioned pedagogies were incompatible with the needs of the musical theater. Nowadays, musical theater specialists routinely give presentations at NATS regional and national conferences, and the organization sponsors an annual Music Theater Competition. Their sponsorship of the development of this volume confirms that the tide has turned at NATS.

“So You Want…” is a book that appears to have been planned by a committee, and in this case, it’s a good thing, since it gives specialists the chance to provide compact, detailed chapters on subjects that have been covered in book length studies on their own. The principal author is Dr. Karen Hall, and her preface quotes a famous lyric by Oscar Hammerstein II, “By your students you’ll be taught.” Faced with the challenge of teaching young students eager to master the musical theater repertoire, she responded resourcefully and re-examined all aspects of her pedagogy. Her philosophy is a pervasive one among the best teachers in our field: there’s jobs to be booked and art to be made here and now, and we owe it to our students to give them the best possible training in the most efficient and effective manner so they can do those tasks well.

“So You Want…” is a book that appears to have been planned by a committee, and in this case, it’s a good thing, since it gives specialists the chance to provide compact, detailed chapters on subjects that have been covered in book length studies on their own. The principal author is Dr. Karen Hall, and her preface quotes a famous lyric by Oscar Hammerstein II, “By your students you’ll be taught.” Faced with the challenge of teaching young students eager to master the musical theater repertoire, she responded resourcefully and re-examined all aspects of her pedagogy. Her philosophy is a pervasive one among the best teachers in our field: there’s jobs to be booked and art to be made here and now, and we owe it to our students to give them the best possible training in the most efficient and effective manner so they can do those tasks well.

Serious voice pedagogues may be surprised to discover how much of this book is actually about repertoire. The first chapter is a brief overview of the history of the musical (one that relies heavily on John Kenrick’s history of the musical), and the book devotes several chapters at the end to lengthy lists of repertoire organized by style and voice type. Those lists are indicative of the bewildering diversity of styles that are part of the commercial musical theater in the present day, and the historical overview helps provide an understanding of why that is the case. Musicals tell stories about all sorts of people in all sorts of worlds, and songwriters have risen to this challenge by creating songs that require many different sorts of vocal technique. What all these shows have in common is the phenomenon of characters expressing themselves through song in dramatic situations, but the singer-actor seeking maximum employability is well advised to pursue proficiency in as many of vocal styles as possible.

A chapter on the singer as athlete by Dr. Wendy LeBorgne (who has just published her own two-volume book, The Vocal Athlete) is full of practical information. Though its tone is a bit clinical for the lay reader, her authorial voice gave me confidence that her recommendations were solidly grounded in scientific fact. Readers of The SAVI Singing Actor will also know that I am much enamored of the singing-actor-as-athlete metaphor, and this perspective is one that I know generations of students have found useful: train to gain, patiently and persistently.

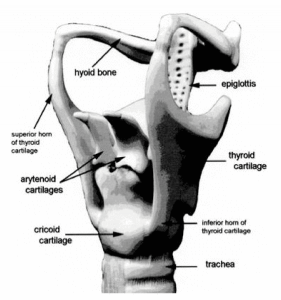

A “how it works” chapter on vocal anatomy by Dr. Scott McCoy provides useful information about the physiological basis of singing. Again, the lingo gets a bit technical, and talk of formants, Boyle’s Law and muscular antagonism may be daunting for the lay reader. This is invaluable knowledge for the teacher, of course, though there’s plenty of Broadway stars who’ve built successful careers without knowing any of this. Is it appropriate knowledge to cover in an undergraduate musical theater course? Given the number of former students of mine who’ve gone on to teach or coach young singers (often alongside a performing career), I think there’s an argument to be made in favor of equipping aspiring singing actors with some rudimentary knowledge of vocal anatomy.

A “how it works” chapter on vocal anatomy by Dr. Scott McCoy provides useful information about the physiological basis of singing. Again, the lingo gets a bit technical, and talk of formants, Boyle’s Law and muscular antagonism may be daunting for the lay reader. This is invaluable knowledge for the teacher, of course, though there’s plenty of Broadway stars who’ve built successful careers without knowing any of this. Is it appropriate knowledge to cover in an undergraduate musical theater course? Given the number of former students of mine who’ve gone on to teach or coach young singers (often alongside a performing career), I think there’s an argument to be made in favor of equipping aspiring singing actors with some rudimentary knowledge of vocal anatomy.

The chapters on vocal pedagogy provide a valuable overview of some of the best work being done in the field. The teaching approaches of Jeanette LoVetri and Mary Saunders Barton are featured prominently, along with other pedagogues like Robert Edwin, Jo Estill and Seth Riggs. Professional practitioners like conductor Lawrence Goldberg and coach/accompanist Robert Marks also provide recommendations that will be of value to students and teachers alike.

One aspect of the book that seemed particularly promising was the availability of supporting material on the NATS website that presented vocalizes, exercises and examples. However, I immediately ran into a dead end when I followed the instructions for accessing the online resources that are supposedly available (“on the NATS Website, click on the ‘Resources’ tab and follow the instructions”), since I couldn’t find the “Resources” tab. I did find a link here (http://www.nats.org/Music_Theater_-_Resources.html) that included some material from the book as well as Spotify links for the listening examples, but it looks like a work in progress. It’s a good idea whose execution is not yet well implemented.

Despite this one complaint, “So You Want To Sing Music Theater” is a comprehensive and useful addition to the literature, a worthy addition to any musical theater singing teacher’s library. It will also has great potential value for the undergraduate student of musical theater, especially those who anticipate finding themselves one day in a teacher’s role. Educators can preview the book on the website of the publisher, Rowman & Littlefield, by requesting an e-inspection copy.