A SAVI Tutorial

In all my years of teaching, I’ve found few techniques more powerful and effective than the one I’m introducing in this tutorial. Generations of singing actors have used it to take their work to new heights of specificity and variety, and it’ll do the same for you!

As you’ll recall, the first axiom of SAVI Singing Acting is:

“When I sing, I will create behavior that communicates the dramatic event phrase by phrase.”

If you understand the power inherent in those last three words – phrase by phrase – you’ll unlock new levels of expressiveness and detail in your performance, and this procedure is designed to help you do just that.

In order to work phrase by phrase, you need to understand where each new phrase begins. In SAVI talk, we call that the “ding” – the onset of the the idea. Identifying the dings, the moments when a new phrase begins, is the first step to working phrase by phrase.

In order to work phrase by phrase, you need to understand where each new phrase begins. In SAVI talk, we call that the “ding” – the onset of the the idea. Identifying the dings, the moments when a new phrase begins, is the first step to working phrase by phrase.

Songs are organized into phrases, a term that refers to both words and music. In most cases, the two work in tandem, shaping the expression of thoughts and feelings into a sequence or series of shapely units. Phrases can be quite short – sometimes no more than a single syllable – or quite long – a dozen syllables or more, stretched out over a span of ten or more seconds, is a very long phrase. A typical phrase, though is just a handful of syllables, arranged to make a statement or ask a question.

I got rhythm

I got music

I got my man

Who could ask for anything more?

The Gershwins’ “I Got Rhythm” begins with four phrases, the first three of which are four syllable statements, parallel in their construction – that is, they all begin with the words “I got” and end with a different two-syllable noun. The fourth and final phrase of the stanza is a question, twice as long (eight syllables) as the previous three phrases. Each phrase presents a unique opportunity for specific expression or communication, and the contrast between the phrases as they unfold is part of how they communicate. “Music” is different from “rhythm,” “my man” is different from either “rhythm” or “music,” and the rhetorical question expressed in the fourth phrase puts the previous three statements in context.

So, in order to unlock the power of phrase-by-phrase interpretation, your first step is to mark the spot in the musical score or the lyric sheet where each phrase begins. In the SAVI System, we use a triangle to mark the “ding,” thus:

∆ I got rhythm

∆ I got music

∆ I got my man

∆ Who could ask for anything more?

(If you’re doing this at the computer keyboard, the triangle symbol is made with the keystroke combination option-J.)

Why a triangle? It’s the Greek letter Delta, the symbol for change. It’s also the picture of the musical instrument that shares the same name as this shape, the triangle, whose sound is a distinctive “ding.”

How do you know when there’s a ding?

- Look at the punctuation of the lyric. Periods, semicolons, commas and dashes can all be signs of a beginning of a new thought.

- Look at the way the lyric is divided up into lines when it’s printed on the page (in the libretto or lyric sheet). This requires you to find a published version of the lyric, in print or on the web.

- Look at the rhythm in the music. Phrases often end with a sustained note followed by a rest, and the first syllable after that sustained-note-and-rest combination is usually the beginning of a new phrase.

- Look for those “little big words” like “but,” “and,” “or,” “except” and other verbal indications that something different is on its way.

- Look for patterns (like the first three lines in “I Got Rhythm”).

There are a variety of clues that will help you discern the dings. The main question you need to ask is, “Is this next word or phrase a continuation of the previous phrase or is there evidence that it’s the beginning of something new?”

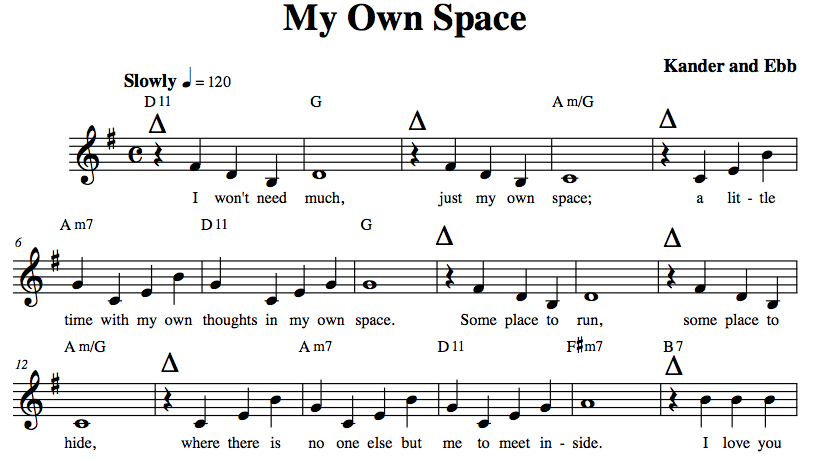

Let’s apply this procedure to “My Own Space,” a song by Kander and Ebb from The Rink. This song was first performed by Liza Minnelli, but here’s a video clip that will give you an idea of what it sounds like. (A young singer from Portland named Danielle Moreland-Ochoa posted it, and while it may not be a “Perfect 10” performance, she’s got some promising ideas.)

I copied the lyric for this song from one of several sites on the internet that turned up in a Google search, but beware! The punctuation and line breaks on such sites do not always reflect the writer’s intentions 100% of the time. I used the sheet music for the song (available from musicnotes.com, a site where you can legally download, transpose and print sheet music) for the most accurate possible version of the punctuation. In the sheet music, there’s no line breaks, since the lyric flows along with the music, and that can fool your eye when you’re doing this sort of work. I’ve adjusted the line breaks in the printed lyric so that there’s just one phrase per line. I recommend that, whatever song you’re working on, you either type out the lyric yourself or take some time to edit it carefully after copy-pasting it from the web.

∆ I won’t need much,

∆ Just my own space;

∆ A little time with my own thoughts and my own space.

∆ Some place to run,

∆ Some place to hide,

∆ Where there is no one else but me to meet inside.

∆ I love you more than I can ever say.

∆ I love you more and more and more with ev’ry passing day.

∆ Allow me light,

∆ A breath of air;

∆ Leave me the only thing I own we cannot share.

∆ Just leave me that,

∆ Sweet love of mine.

∆ Just leave me that,

∆ Just my own space,

∆ And we’ll be fine.

Look at the rules I’ve provided and see if you follow the way I marked the dings. Now take a look at the first few lines of the sheet music with the dings marked in:

You’ll notice that I’ve placed the triangle mark over the beat preceding the first syllable of the phrase. This is because the thought has to come before the word, just like in real life: the idea precedes the verbal expression of the idea by a brief instant.

Dings in Place – Now What?

The procedure I’ve described in the steps above will help you identify the ideal moments for you to adjust your behavior. To create behavior that communicates the dramatic event phrase by phrase, the best thing you can do is make an adjustment in your behavior at the onset of each new thought – in other words, at every “ding.” The adjustment you make can take any number of forms:

- a change of focus (look somewhere else)

- a change of facial expression

- a change of gesture

- a change of stance or body language

- a change of location (move somewhere else)

- a change of volume

- a change of timbre (or other vocal choice)

You don’t have to do all of these things at every ding; just one will suffice. The changes don’t have to be exaggerated, but they need to be specific, thoughtfully chosen, and carefully coordinated with the musical timing of the song.

Take another look at Danielle’s video and see if you can identify the moments when she makes an adjustment, a specific decision to create new behavior. You can see it at 0:41, the beginning of the phrase “Some place to run” (though ideally she’d make that focus shift a moment earlier, before the onset of the new phrase). She mobilizes her eyebrows and varies her facial expression to good advantage during the following seconds, and makes a clear and well-coordinated shift at 0:50, on the lyric “Where there is no one else…”

If you think you understand the procedure, then try it out on a song you’re working on now. If you’re confused, leave a question in the comments area below and I’ll answer it right away.