Inspiration often comes from unexpected places, but I bet you never imagined that a Furby could teach you something about the craft of singing acting!

Inspiration often comes from unexpected places, but I bet you never imagined that a Furby could teach you something about the craft of singing acting!

Millions of these little guys have been sold since the Furby was first introduced in 1998. One of the secrets of this animatronic toy’s success is how it makes you want to interact with it. In a recent segment on the always-fascinating Radiolab podcast, Caleb Chung, one of Furby’s designers, described three principles that guided his efforts to make a toy that will engage children in immersive play:

- It has to show emotion

- It has to be responsive to its environment

- It has to change over time.

Furbys have to be super-simple to exhibit engaging behavior with a handful of chips and servo-motors, and these principles are super-simple, too. But does the behavior you exhibit in your singing acting pass the Furby test?

1. Showing emotion.

Designer Caleb Chung learned the art of emotional expression from his early days working as a mime performing on the streets. He understood that expressive behavior was a kind of vocabulary. Changing the tilt of your head or the lift of your ribcage can signify a thought or feeling. When it came time to create Furby, he used his street-performer’s insights to determine how Furby would move its eyes and ears.

Take a look at the photo of Furby, and notice what strikes you right away. It’s those big eyes, of course! The eyes are featured prominently in Furby’s expressive repertoire. The more recent models of Furby have LCD eyes where the pupils are a digital display, while the old-school models like the one pictured above have painted eyeballs. Regardless of the technology used, however, the eyeballs and the eyelids both move, and that gives the toy an uncanny expressiveness.

So – a toy designer with super-limited resources chose to make moving eyes a prominent feature in his creation. How do you use your eyes when you sing? Do you gaze off vaguely into space? Are your eyes glazed over because of stress or fear? The SAVI singing actor understands the importance of eye language, and realizes that, in order to communicate effectively, you have to mobilize your eyes! Use your phone or a camera to record your face while you sing, and take stock of your eye language. I’ll bet it could use some work.

Of course, there’s more to expressing emotion than wiggling your eyeballs, but you’d be amazed how many singers neglect this basic element of communication and how profound an improvement it can bring to your performance. Facial expression, gesture, stance and other components of non-verbal communication also play an important role in your performance, and you’ll want to activate them all for an optimal performance.

2. Responsive to the environment.

Furby creates the illusion of being interactive by being responsive to sensory information. Make a loud noise, and Furby will cry out; poke him and he’ll laugh; turn him upside down and he whimpers with fear. None of this would happen if Furby’s sensors weren’t continuously active, taking in data from the environment.

Making your senses more alive is one of the key ways you can bring greater truth and believability to your singing acting performance. Too often, singers get hyper-focused on OUTPUT – especially the sounds they are making – and don’t take in any INPUT. It’s like breathing out and breathing in – you can’t have one without the other. If you take in some sensory data, it’ll make a change in the behavior you express.

This is tough for the singer who is performing solo in a classroom, club or concert. There’s no scene partner to respond to, no environmental cues to stir your senses. You’ve got to use your practice time in ways that stir your senses so that you build up your expressive vocabulary. Look at meaningful photos, inhale some stimulating smells, work with a partner, handle props and objects that provide tactile stimulation – there’s all sorts of ways you can “come to your senses!”

When you are playing a scene with a partner, you get all sorts of signals that you can used to bring your performance to life. Treating a solo song as a conversation with an “imaginary partner” is a powerful strategy, but give your “imaginary partner” some provocative lines and actions so that you’ve got something useful to “react” to.

3. Change over time.

Furby’s creator observed that living things don’t always act exactly the same, and built changes into his creation’s behavior so that children playing with the toy would stay interested and engaged. Not only does he respond to stimuli like tickling and loud noises, but he uses more English words (as opposed to “Furbish” gibberish) as he gets older. If Furby did the same thing all the time, he’d be boring, and certainly not lifelike!

So what does this tell you about singing acting? Too many singers get “stuck” in a general attitude or mood, and don’t make new choices that produce behavioral change as the song goes along. Sometimes the simplest change is all you need – shift your focus, vary your volume, adjust your stance. Change creates a quality of lifelike authenticity and increases your spectators’ engagement with your performance. What’s more, change creates meaning – when you do something different, your spectators can’t help but think, Wow! That’s different! I wonder what’s up with that?

In the SAVI studio, I use the term “applesauce” to describe a performance without changes. Applesauce is delicious, but every bite is exactly the same. You need to serve up a varied menu, a “shish kebab” of varied flavored and textures, and this means analyzing the song to determine what the writers have done to vary the song phrase by phrase.

In the SAVI studio, I use the term “applesauce” to describe a performance without changes. Applesauce is delicious, but every bite is exactly the same. You need to serve up a varied menu, a “shish kebab” of varied flavored and textures, and this means analyzing the song to determine what the writers have done to vary the song phrase by phrase.

Tension is the enemy of change, and that’s probably the biggest reasons why singers get stuck. When you’re singing onstage, you shift into “fight or flight” mode, same as you would if you were facing a threatening predator. Your so-called “lower brain,” where your instinctual behaviors are controlled, causes hormones like cortisol to be secreted when you’re under stress. Your body braces up, your senses become highly focused (screening out all but the most important stimuli), and you experience what seems like a burst of energy. The “fight or flight” response robs you of your ease, and ease is what you need if you want to remain responsive and truthful.

Be like Furby?

Don’t think for a minute that I believe you should imitate a robotic toy to be a successful singing actor. The human organism is far more sophisticated than a Furby toy, and your human qualities have to be on full display to be a successful singing actor. However, a lot of thought went into simple things that Furby could do to create the illusion of being life-like and engage children in immersive play. Try a trick or two from Furby’s repertoire and see if it doesn’t bring new expressiveness to your singing-acting!

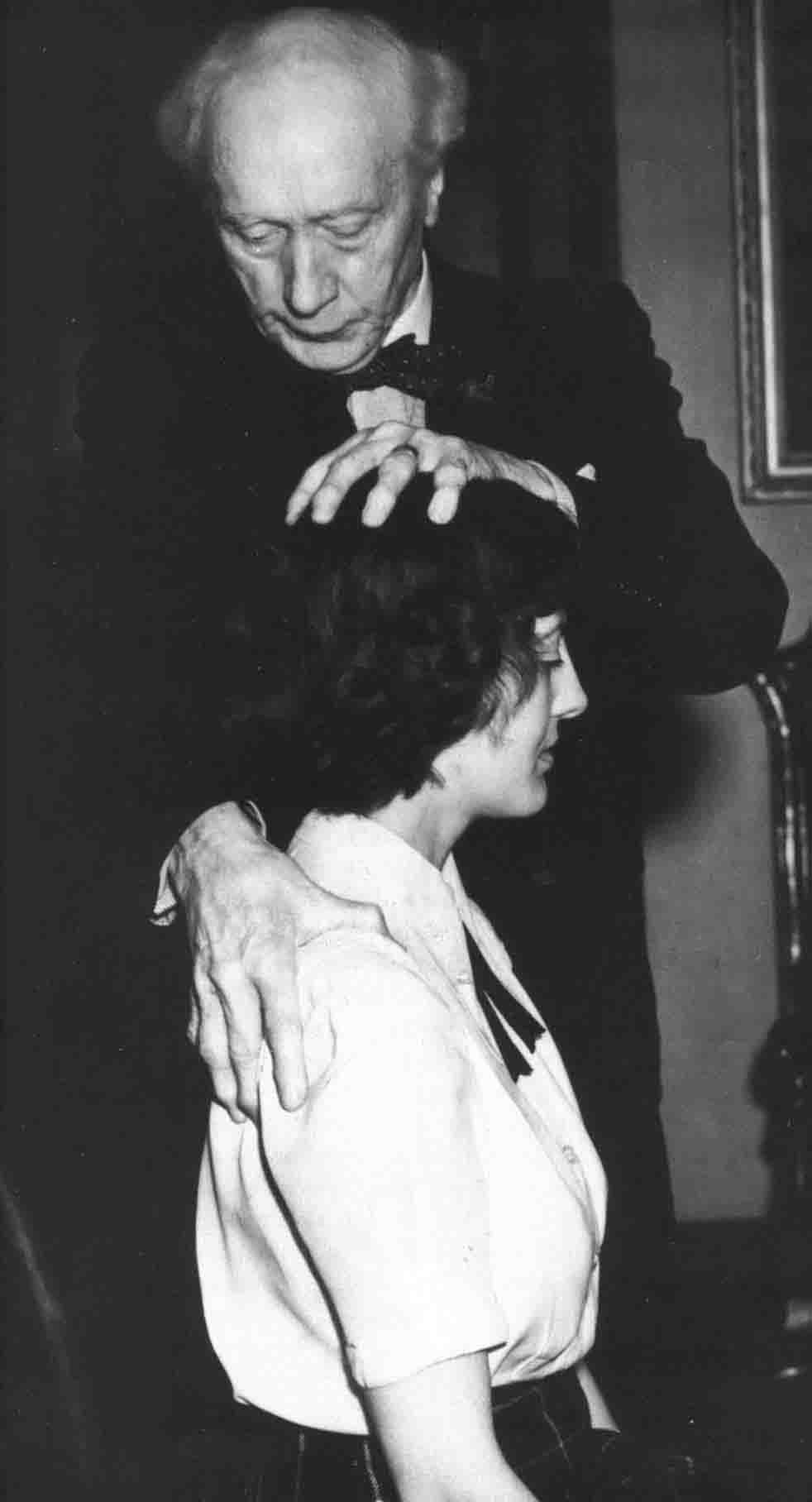

Many performing arts schools include training in Alexander Technique as part of their program of studies, and many performing arts teachers have had some training in Alexander Technique. Alexander Technique focuses on how we use our bodies, particularly at times when we are under pressure to do something stressful or challenging, and this makes it especially useful to singers, actors, dancers and instrumentalists seeking to improve their performance. AT helps the student become aware of unconscious physical habit patterns that add unnecessary tension and effort, and re-educates performers to achieve more optimal use of their bodies. AT has benefits that extend to people in all walks of life, and many individuals have derived great therapeutic benefit from the technique. Performers who are able to incorporate the Alexander Technique notice greater poise and ease, less pain and tension, and an expanded sense of possibilities.

Many performing arts schools include training in Alexander Technique as part of their program of studies, and many performing arts teachers have had some training in Alexander Technique. Alexander Technique focuses on how we use our bodies, particularly at times when we are under pressure to do something stressful or challenging, and this makes it especially useful to singers, actors, dancers and instrumentalists seeking to improve their performance. AT helps the student become aware of unconscious physical habit patterns that add unnecessary tension and effort, and re-educates performers to achieve more optimal use of their bodies. AT has benefits that extend to people in all walks of life, and many individuals have derived great therapeutic benefit from the technique. Performers who are able to incorporate the Alexander Technique notice greater poise and ease, less pain and tension, and an expanded sense of possibilities.