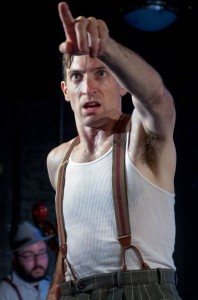

Eleanor Roosevelt once said, “Do one thing every day that scares you,” and Philadelphia actor Ben Dibble clearly has taken the former First Lady’s advice to heart. Known around town for his versatility and his chops as well as his sang froid, the plucky Dibble acknowledges he was plenty scared by the challenge of Herringbone, an unusual, little-known musical produced by Flashpoint Theatre Company earlier this summer. “This show … scared the living s@&t out of me,” he confessed to his Facebook friends, and in a pre-opening interview, he described it as “more nerve wracking that most shows I’ve done.”

Eleanor Roosevelt once said, “Do one thing every day that scares you,” and Philadelphia actor Ben Dibble clearly has taken the former First Lady’s advice to heart. Known around town for his versatility and his chops as well as his sang froid, the plucky Dibble acknowledges he was plenty scared by the challenge of Herringbone, an unusual, little-known musical produced by Flashpoint Theatre Company earlier this summer. “This show … scared the living s@&t out of me,” he confessed to his Facebook friends, and in a pre-opening interview, he described it as “more nerve wracking that most shows I’ve done.”

Then again, who wouldn’t be daunted by a musical in which you have to play ten different roles, by yourself, without ever leaving the stage?

Dibble’s efforts were rewarded with a unanimous chorus of praise, and standing ovations became routine at the Off-Broad Street Theater. “All hail Ben Dibble!” trumpeted critic Neal Zoren.”‘Tour de force’ is too light a praise to let it suffice to encompass all this brave, virile, agile, expressive triple threat performer. … Ben Dibble … did everything but swallow fire and prepare a soufflé. I’d bet neither of those tasks would daunt or distract him.” Toby Zinman of the Philadelphia Inquirer concurred: “Ben Dibble giv[es] a performance of stunning virtuosity,” she observed, adding, “Everybody who goes to the theater regularly in Philadelphia knows Dibble’s range, from Shakespeare to children’s shows; he sings, he dances, he acts in comedies and tragedies. But in Herringbone, he does it all at once, playing multiple characters–dead and alive, male and female, old and young– while narrating the story.”

Okay, reading rave reviews for a show that’s already closed is a poor substitute for first-hand experience, but take my word for it: it was a rare occurrence to see work this masterful, and the experience leaves one feeling privileged and stirred. In my case, proud, too, since Ben is a former student, and though I can’t take any credit for his remarkable talent, I could see the evidence of his training in the technical mastery he displayed onstage nightly. The work Ben did in this production was the embodiment of everything I teach about singing acting, and there’s much to be learned by examining the creative process with the artist himself.

I asked Ben what his thoughts were when he realized the challenge he’d gotten himself into with this show, and he replied:

I spent a good part of May reading the script and having no idea how in the world I was going to tell this story. I wanted to learn the script in advance, but felt quite blocked and overwhelmed. The first several days of rehearsal as we read and sung the show, I think [director] Bill Fennelly, [music director] Dan Kazemi and I were all putting our best game faces on while inwardly trying not to panic over what seemed an impossible puzzle to solve.

So how does one go about the task of preparing a performance this complex? Each character required a distinctive vocal, facial and physical characterization, and many scenes called for Dibble to switch characters frequently and instantaneously. What’s more, one character, an eight-year-old boy, is “possessed” by the ghost of a middle-aged actor, and the ghost’s voice appeared at times to come from the boy’s body as the action culminated in a the climactic battle of wills between the two. As you can imagine, diligent preparation and patient drill went into the crafting of each moment, so that the sequence of individual moments could be executed with dexterity and panache. Looking back on the process of preparing to play the role, Ben recalls:

I think the key for this show for me was finding the voice for each character. Once we locked in on certain cadences, timbres and accents (guttural rural drawl for Arthur, plantation lilt for Louise, etc.) then the physicality became more apparent. And once I was able to find keystone physical shapes (fanning of the face for Louise, suspenders for the lawyer, thumbs in pants for Arthur, etc.) then the scenes started to make sense to me as they played out. Bill was really astute to keep my movement through space economical. At first I was trying to act each character where they would be in the given room, but that quickly became too much and Bill kept encouraging me to keep the scenes open and let the audience follow my shifts as part of the joy within the structure.

In a scene early in Herringbone, the aged vaudevillian “Chicken” Mosley tries to teach eight-year-old George how to be a performer, and the process is mechanical and laborious at first: one word, one step, then the next. Performing in a musical is nearly always like this, mechanical at first, as one struggles to learn the songs (fiendishly complicated in this case), memorize the text and master the staging and choreography. After a bit, the execution of the “routine” (a vaudeville term that seems particular fitting here) becomes more flowing and requires less conscious thought – more “routine,” as it were. Relegating the mechanics of a performance to the “background,” where mental processing is nearly automatic, is like mastering the skill of driving a car; as you gain proficiency, the activity requires less conscious thought, leaving you free to devote more of your attention to other things. In this case, it allows the actor to fill the words, melodies and movements with emotional truth and focus on bringing the story to life.

“The art of making art,” observes Stephen Sondheim, “is putting it together, bit by bit,” and that’s a fitting description of the process Dibble undertook in collaboration with director Bill Fennelly and the “Herringbone” creative team. “Every little detail plays a part” in Dibble’s performance, from a flick of the eyes to a flutter of the hand. I asked Ben to describe a couple favorite moments from the show, and he replied:

“The art of making art,” observes Stephen Sondheim, “is putting it together, bit by bit,” and that’s a fitting description of the process Dibble undertook in collaboration with director Bill Fennelly and the “Herringbone” creative team. “Every little detail plays a part” in Dibble’s performance, from a flick of the eyes to a flutter of the hand. I asked Ben to describe a couple favorite moments from the show, and he replied:

One of my favorite scenes is a scene in Act II that takes place entirely at the (invisible) mirror where I use only my face and voice to depict the character changes while putting on eye makeup. When Bill told me this idea I felt terrified and exposed. He kept telling me to slow down and trust that facility and pace was not helpful, which was hard for me to do. Once we found the rhythm I came to absolutely love the power of taking the audience deep into the first big psychological turns. I also love the Louise number. After keeping the show so compressed and leaping from one character to the other, it is such a release to be myself and just sell the hell out of a real showstopper. And I added some of my own riffs up to show off a little of my high notes, which makes it a total blast to sing (even though I am still managing my breath as I get winded from the choreography!)

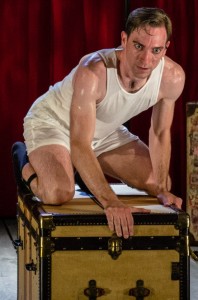

How hard is it to allow yourself to become emotional while executing a demanding score of musical and behavioral details? In a particularly memorable scene, little George finds himself in a hotel room with a floozy while the spirit of The Frog, the ghost who possesses him, tries to use the lad’s pre-pubescent body to consummate a tryst with the woman. It’s a musical trio in which each of the characters – the boy, the Frog and the woman he has marked for conquest – have distinct character traits and strongly differing points-of-view. Dibble delineates each one masterfully – the urgent, grotesque desire of the Frog, the panic and confusion of the innocent boy, and the woman by turns charmed, aroused and bewildered by a seducer who looks like a child and sounds like a satyr. We hear from each in turn as Dibble writhes and changes positions, passionate and yet precise, building to a climax that left the audience hushed and shattered. I asked Ben what went through his mind during the scene with Flo in the hotel room, and how he managed to balance technique and emotion in a scene like that:

How hard is it to allow yourself to become emotional while executing a demanding score of musical and behavioral details? In a particularly memorable scene, little George finds himself in a hotel room with a floozy while the spirit of The Frog, the ghost who possesses him, tries to use the lad’s pre-pubescent body to consummate a tryst with the woman. It’s a musical trio in which each of the characters – the boy, the Frog and the woman he has marked for conquest – have distinct character traits and strongly differing points-of-view. Dibble delineates each one masterfully – the urgent, grotesque desire of the Frog, the panic and confusion of the innocent boy, and the woman by turns charmed, aroused and bewildered by a seducer who looks like a child and sounds like a satyr. We hear from each in turn as Dibble writhes and changes positions, passionate and yet precise, building to a climax that left the audience hushed and shattered. I asked Ben what went through his mind during the scene with Flo in the hotel room, and how he managed to balance technique and emotion in a scene like that:

Great question. This play is structured so specifically as to help the actor; even in its extremity of emotion and rapidity of character changes there is a logic to the way the scenes play out. Bill was incredibly helpful the day we staged the hotel scene of finding the thread that would keep clarity and allow me to really live in each moment. It took a long time for me to know it well enough to let it flow and trust that the next words would come out of my mouth! And I like to always find the infrastructure of a given scene or song (music, physical shape, vocal range) first because then I feel free to let the emotional life arise in a visceral way.

Ben’s search for the “infrastructure” of the scene is a process that begins with externals (music, voice and body) which, in time, unlock the key to an inner life. In other words, it’s an “outside-in” process, one that the best singing actors endorse. While this may seem contrary to the “inside-out” process advocated by actors working in the Stanislavski tradition, my experience suggests that these two approaches are complementary, not contradictory, and that the singing actor is well-served by a technique that recognizes the value of both.

A one-man show presents challenges of stamina and endurance that a performer doesn’t encounter doing a more typical show. There’s never a moment to relax, never a moment when the show doesn’t rest entirely on your shoulders. Describing the challenges of performing the show repeatedly, nightly, over a period of time, Ben said the key issues were:

Stamina and pacing! You could easily give an entire show’s worth of vocal and physical energy in the first act, and have nothing left for the emotionally draining second act. I really had to keep in touch with my whole physical instrument in a moment-to-moment way during the performance to know “hey, you are over-singing cuz you have friends here-ease up” or “you are dragging the pace and your legs are tiring…dig in pal!” In some ways the constant activity of the show is helpful as I never have a chance to worry about my mistakes or how much show is still in front of me-it is the most in-the-moment I have ever been on stage, which has been really liberating.

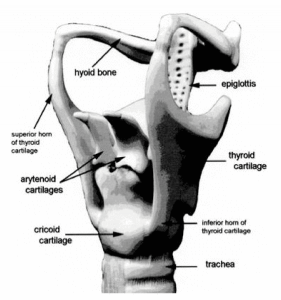

However, with repetition comes efficiency and greater ease, and Ben found the show easier to do as the run progressed. He took advantage of this opportunity to explore individual moments more fully, curious about how far and how deep he could go with their content. Of course, good health and self-management are key under these circumstances. Ben got a little panicked when he discovered his “cords getting a little crunchy” after a grueling three days that included four shows plus three ninety-minute master classes for high school students. The father of three, he was also alarmed to experience symptoms of a cold that was affecting his young children. It required enormous mental focus and the life-style of a monk to survive a feat like Herringbone. Looking back on the entire experience, Ben says he feels

Very proud and grateful. I would never have sought out this role, and now I can do it and it feels so affirming to climb this mountain of a role and survive. There is no role that could scare me right now. And I guess it says something about my unique gifts as a performer if my most iconic roles to date are Bat Boy, Toad and Herringbone. And this team, with Bill and Dan and [choreographer] Jenn [Rose] in particular, was a dream team. I could never have flown in this without their artistry and support.

I owe a thousand thanks to Ben for his thoughtful responses to my questions, along with a chorus of huzzahs in recognition of his accomplishments. I know that Ben and Bill are exploring the possibility of recreating this production of Herringbone at other regional theaters, and maybe you’ll be lucky enough to see it yourself one day.

I’ve got a new favorite catchphrase – “Just do your bits” – and it comes from a fascinating profile of the comedian and actress Maria Bamford that appeared in the

I’ve got a new favorite catchphrase – “Just do your bits” – and it comes from a fascinating profile of the comedian and actress Maria Bamford that appeared in the